[From my submission to the Voice of Olympia]

Sometimes I am struck by the nostalgia I feel for the way that French fries wore themselves into the carpet at the Denny’s in

I first ran away from home when I was fifteen. I had started using drugs, fighting – sometimes violently – with my parents, and skipping school. As I became more rebellious, my parents became stricter, and our arguments escalated.

One night I finally got fed up, packed a backpack, and climbed out my bedroom window. Things had been particularly ugly at home, and my parents, foreseeing the possibility that I might run away, had taken my shoes. I walked barefoot for several miles to a bonfire party that a friend was throwing in the woods. I got drunk and slept outside. Two days later, a friend in Yelm took me into her home and let me stay for a month and two weeks.

My parents tracked me down, took me to court, and had me placed on the “Youth-At-Risk” program. The judge ordered me to return home, obey a curfew, speak respectfully to adults, keep my grades up in school, avoid certain friends… The list of rules was lengthy, and failure to obey would result in being charged with “contempt of court”, a misdemeanor.

As my term in the “Youth-At-Risk” program came to an end, my parents motioned the court to renew my participation. I had already racked up two counts of contempt for breaking the rules, and the tension between my parents and I had grown thick. I decided that I would not tolerate living at home any longer. I packed a small backpack and a gym bag, snuck out my window again, and hitchhiked to

I was aware that I couldn’t go back after leaving. I was still court ordered to remain at home, and if I had returned my parents would have reported me to the police.

At first I was overwhelmed by the sense of finality, and loneliness. My safety net had fallen away and I felt as though I was suspended mid-air, grasping tightly to a thin line of fraying yarn that prevented me from falling. Anxiety pushed stiffly outward from within my chest, hampering the flow of air into my lungs. I was on my own, and the noisy, sinister world and an uncertain future loomed overhead, shrouded in the cold Pacific rain.

I learned to panhandle pretty quickly. I panhandled for food, for cigarettes, and for pot. Panhandling is a lot like hitchhiking. You have to be in the right spot. You have to look un-intimidating. Occasionally someone will screech their tires driving past or throw something at you while you are trying to thumb a ride. Sometimes people will make rude remarks or spit at you when you try to spange money for lunch. At least with hitchhiking there is a sense of adventure. Panhandling was just humiliating.

I was lucky to have a number of friends in the

On my seventeenth birthday, a friend took me out to stay at his cabin on

I had never bought my own groceries before. Everything I had was unearned, a gift from someone like my parents or the people who gave me change when I panhandled. The spaghetti was good, made from scratch with fresh tomatoes and herbs, but the experience of having earned it was far better.

A month later, my buddy Jeremy let me move into his camper out in the woods on the outskirts of Yelm. I started getting a lot of work splitting firewood and digging ditches. I had quit smoking pot, and was starting to get my energy back. I made enough money to start renting, and I got my first full time job three days before my eighteenth birthday.

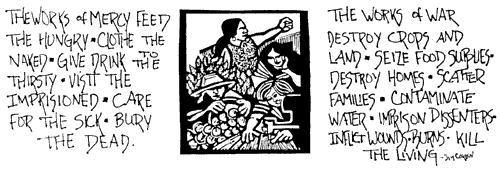

In the time since I was homeless, I've worked two years as an EMT for an ambulance company, graduated from the WA State Fire Training Academy, spent three years as a volunteer firefighter (and I nearly got hired on a professional department), and owned a home that I later sold to pay for college. I've spent the last three years as a live-in staff person at the Bread & Roses Catholic Worker Community.

No comments:

Post a Comment